...Who Made Me a Woman

“Blessed art Thou, O Lord our God, king of the universe, who did not make me a woman.” Jewish men have recited this blessing for centuries. Jews are not the only people who have said blessings of this type. Socrates, or perhaps Thales, we are told by Diogenes Laertius in his Life of Thales, may have repeated three blessings for which he was grateful to fortune: “First, that I was born a human being and not one of the brutes; next, that I was born a man and not a woman; thirdly, a Greek and not a barbarian.”

Jewish women, at the same point in the morning prayers, bless God “who made me according to His will.” In our own time, Conservative, Reconstructionist, and Reform Judaism have changed or eliminated these blessings, but Orthodox prayerbooks maintain them as they have always been.

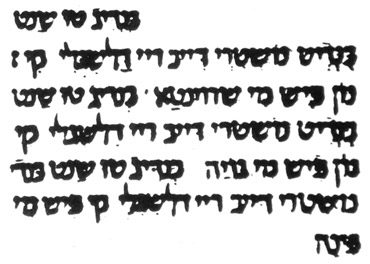

Always? No. There is at least one exception: Roth Manuscript 32, a 14th- or 15th-century translation of the daily prayers into Shuadit, which was the language of the Jews of southern France until the early 19th century. Shuadit is also called Judeo-Provençal and was very similar to the local language spoken by non-Jews in the south of France. The prayerbook was written in the Hebrew alphabet. Below is an image of a passage from the prayerbook.

Here, in my own transcription into Latin characters, are three blessings from the Morning Benedictions (Birkhot ha-Shahar):

Benedich Tu Sant Benezet nostre Diew rey dal segle

ke non fis mi serventa.

Benedich Tu Sant Benezet nostre Diew rey dal segle

ke non fis mi goya.

Benedich Tu Sant Benezet nostre Diew rey dal segle

ke fis mi fena.

The English translation is as follows: Blessed art Thou Lord our God king of eternity who did not make me a slave (feminine). Blessed art Thou... who did not make me a Gentile (feminine). Blessed art Thou... who made me a woman.

The book that contains these blessings is one of many examples of a Renaissance translation of the prayerbook into the vernacular. The vernacular could be any language at all, but the alphabet had to be Hebrew. The Jews of southern France have left us very few documents in their language. To my knowledge, only one copy of the Shuadit translation of the prayerbook exists in the world. It is found in the Brotherton Library at the University of Leeds, England, and was donated by Cecil Roth. The title page bears the Hebrew words ahoti at hayiy le-alfey revavah, “my sister, be the mother of thousands of ten thousands,” based on the blessing to Rebecca in Genesis 24:60 and suggesting that the translation was a wedding gift to a sister. The book, at least for a time, belonged to a family named Montel, which is the Provençal equivalent of the French-Jewish surname Monteux.

Many translations of the prayer-book were explicitly made for women. Men, ideally, could read and understand the service in Hebrew. Jewish women were also expected to read. They had to learn Hebrew in order to say their prayers. But they did not always know enough Hebrew to understand what they were saying, and so translations were written for them. Any woman who knew Hebrew letters could sound out the words of her own native language. I rather suspect that a good many men also needed and made use of these vernacular prayerbooks. Italy in particular is a place that has given us prayerbooks of this type. There are handwritten copies dating from the 14th and 15th centuries, and printed versions, which went into several editions, dating from the 16th. Copies may be found in the British Museum, the Special Collections Library of Columbia University, the Jewish Theological Seminary, and other libraries in various countries. The existence of so many translations of religious texts made for women in the Renaissance shows that Jewish women could read during an era of widespread illiteracy.

My interest in Roth Manuscript 32 is linguistic and not liturgical. But when I came across the words, “who made me a woman,” I was very surprised. I looked at the Liturgy Collection of the Jewish Theological Seminary to see if there were parallels in other prayer-books. I found none, although I came across one work (MIC 4266) dating from 1776 where the scribe was a woman, Esther bat Joseph Rovigo. In a Judeo-Italian prayer-book for women (MIC 4076) there was only the familiar "who made me according to His will," which in 15th-century Judeo-Italian was “che fece mi come la volentade Soa.”

People who speak Italian will notice the unusual word order, che fece mi instead of che mi fece and la volentade Soa instead of la Sua volontà. Similar peculiarities are found in the Shuadit examples cited above. That is because medieval and Renaissance translations were done word for word. Hebrew word order was followed slavishly even if the result was ungrammatical or meaningless. Thus we have "king of eternity" instead of “king of the universe” in the Shuadit blessings above. The Hebrew 'olam can mean either “eternity” or “universe,” depending on the context. Medieval translators, however, paid no attention to context. Each word had one and only one translation, whether it made sense or not.

If our translation was super-literal and word for word, how can it say “who made me a woman”? Is there a Hebrew original? Perhaps, but I have never seen one or heard of one. There is no reference to such a blessing in Ismar Elbogen's Der jüdische Gottesdienst in seiner geschichtlichen Enlwicklung ("Jewish Liturgy in Its Historical Development"), or in Joseph Heinemann's expanded notes to Elbogen. Asher of Lunel (in southern France) apparently never referred to a special women's blessing according to the discussion in Saul Lieberman's Tosefta Kifshutah. A recent article in Sinai (1979) by Naphtali Wieder on the blessings “Gentile, slave, woman” does not mention anything concerning a unique women's variant.

But I am not the first scholar in recent years to have looked at Roth Manuscript 32. Moshé Lazar published an article in Melanges offerts à Jean Frappier in which he discusses this manuscript, transcribes part of it into Latin letters, and translates the transcribed sections into French. In Lazar's article we read, “...qui m'a faite femme.” Yet Lazar does not comment on the uniqueness of this passage; his article is about the language of the text but not its content. Unfortunately, scholars of liturgy, who would be very interested in a previously unattested variant of the Morning Benedictions, do not ordinarily read about Romance philology, and so it is doubtful that they are aware of Lazar's article. Perhaps certain scholarly discoveries belong in magazines of general interest as well as in learned journals.

Although the Morning Benedictions are generally taken from Talmud Berakhot 60b, the women's blessing, “who made me according to His will,” may not be very much older than our Shuadit translation. Israel Abrahams, in A Companion to the Authorized Prayerbook, says that it was attested in the first part of the 14th century. Conceivably there were competing variants in the Middle Ages, only one of which has survived to our own time. The Shuadit version, unfortunately, did not make it.

“Blessed art Thou... who made me according to His will” would be an egalitarian blessing if it were said by both men and women. It is considered evidence of an inferior religious status for women because it does not balance the corresponding men's benediction. For that matter, neither does the positively phrased "who made me a woman," but it reflects greater pride and seems to suggest a view of the religious role of women as equivalent to that of men. Why then do we have no other evidence of its existence?

Can it be that it was written once and only once, in a work commissioned by an important man who wanted an especially nice blessing for his sister to be included in the book he gave her as a gift? If that were the explanation, our prayerbook would be unique in history and could tell us nothing about the possibility of an alternative tradition of women's blessings in the Morning Benedictions. It would also mean that Jews in the 14th or 15th century felt free to alter the prayers as they wished, a possibility that is very unlikely indeed, especially in view of the extreme literalness of our translation.

Was there a degree of equality for Jewish women in the Middle Ages and Renaissance that has vanished from the liturgy? There is no evidence. All we have is the fact of a single blessing in a translated prayerbook from southern France. Conjecture is valuable and pleasurable, but there is nothing so beautiful as a fact.

A version of this essay appeared in the April 1981 issue of Commentary.

Home | Language | Politics and Religion | Autobiography | Music and Poems | Miscellaneous | Contact | Links